The Forgotten Story of Two Public Lynchings

I did some research during our short stay in Springfield, MO this week. I jotted down a few thoughts about a significant, yet buried bit of history I discovered:

On Saturday, April 14, 1906, two young black men were lynched in the public square downtown Springfield, MO. Executed for a crime they did not commit. A white couple had allegedly been attacked, the woman raped, by two masked men whom the victims could not identify.

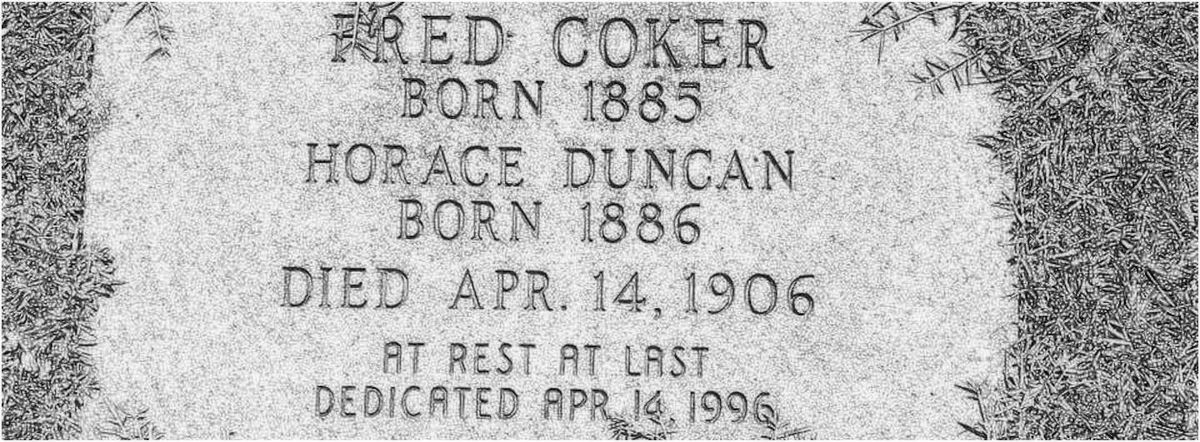

With that limited information, Fred Coker and Horace Duncan, both age 20, were arrested on April 15. It was Good Friday. The men were released after their employer showed up to the jailhouse and testified that they had been loading freight all night when the alleged crime took place. The men were released immediately, but they were arrested again the next day, reportedly for “their own protection”.

Rumors swelled that a lynch mob was forming. The rumors proved true, and the angry, drunken mob descended on the jailhouse that evening, overpowered the sheriff, and seized the two inmates.

They marched the men down to Park Central Square and hung them from Gottfried tower, at the top of which ironically stood a whitewashed replica of the Statue of Liberty.

As Fred and Horace suffocated by noose, their bodies were doused in coal oil, and a fire was lit at the base of the tower. When the fire rose and burned through the nooses, their charred, already dead bodies dropped into the fire.

By 11:40pm, the two men were a pile of ashes at the feet of Lady Liberty.

It is believed that up to 4,000 people were in attendance to witness this event. When it was all over, the spectators picked through the ashes to retrieve “souvenirs” in the form of bone fragments, scraps of clothing, and even charred flesh.

The next day, a local undertaker came and shoveled what was left of the remains into a pine box for burial in an unmarked grave in the black section of Hazelwood cemetery.

This morning, I visited Hazelwood Cemetery and went up and down the aisles looking for the place where Fred Coker’s and Horace Duncan’s ashes were laid. Thanks to a group of local high school students, the gravesite now has an in-ground headstone.

It took me a little while, but I found it. And it mattered to me to find it. To see their names etched in stone. To stand where their families once stood in mourning. To give them a little bit of my time. To keep their story alive.

When the sun rose the morning after the lynchings, it was Easter. The vast majority of the townspeople put on their Sunday’s best, filled the pews of their churches and sang hymns to the risen Savior. Meanwhile, most of the city’s black population, stricken with fear, packed up their belongings and headed out of town for good.

Almost overnight, Springfield’s black population dropped from about 20 percent to 2 percent. That number has never risen back above 4 percent.

This single event forever changed a city where their had been a thriving community of successful black citizens. They closed their businesses. They abandoned their churches. They never came back.

(This is only part of this story. I may expand this at a later date. Stay tuned. Or Google “April 14 1906 lynchings” to read up on it yourself.)