My Family History is Now a Brand at Target

The enslaved women of Gee’s Bend pieced together scraps of fabric to make quilts in abstract patterns. The patterns and piecing styles were passed down over generations, surviving slavery, reconstruction, and Jim Crow. Now they’re in Target stores.

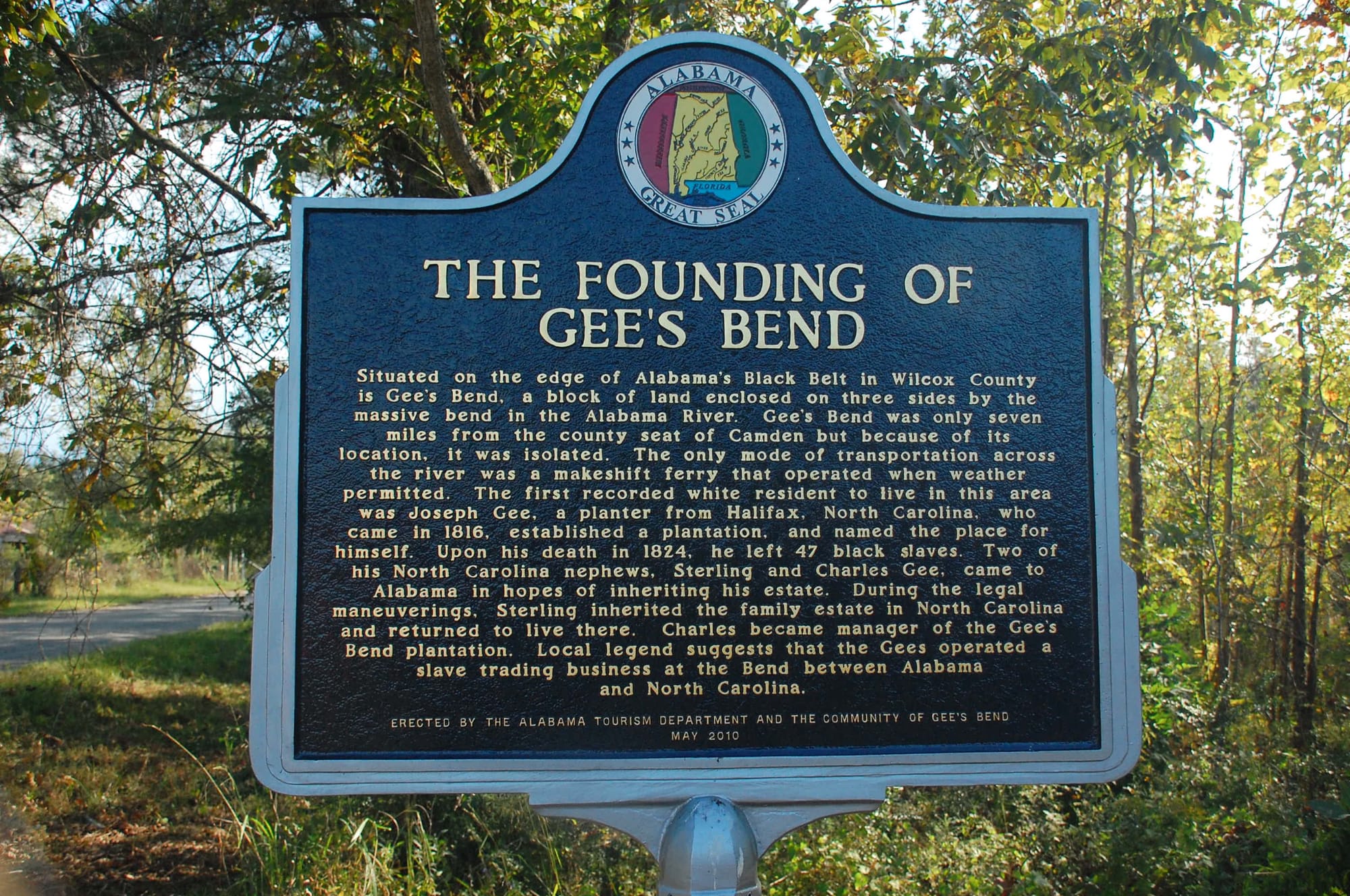

In 1845, Mark H. Pettway received a plot of land in Alabama’s Black Belt after settling a $29,000 debt with his relatives, Sterling and Charles Gee. The land was called “Gee’s Bend”. Pettway packed up and moved to Alabama from North Carolina with over 100 of his slaves. With the exception of one cook, the slaves walked from North Carolina to Gee’s Bend, just southwest of Selma. A Trail of Tears you certainly never learned about in grade school.

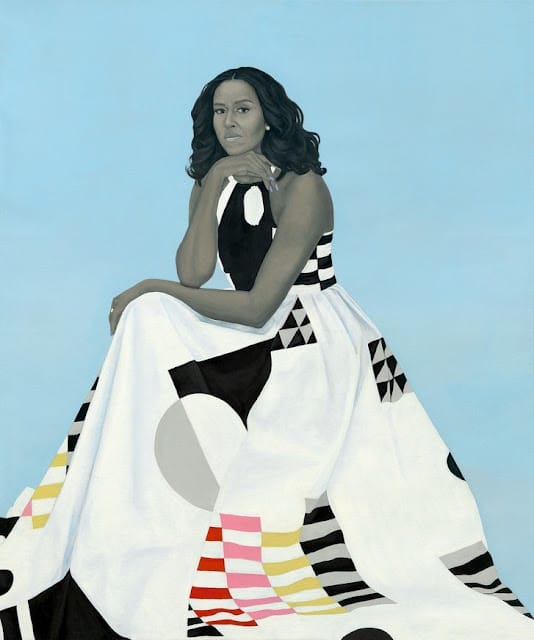

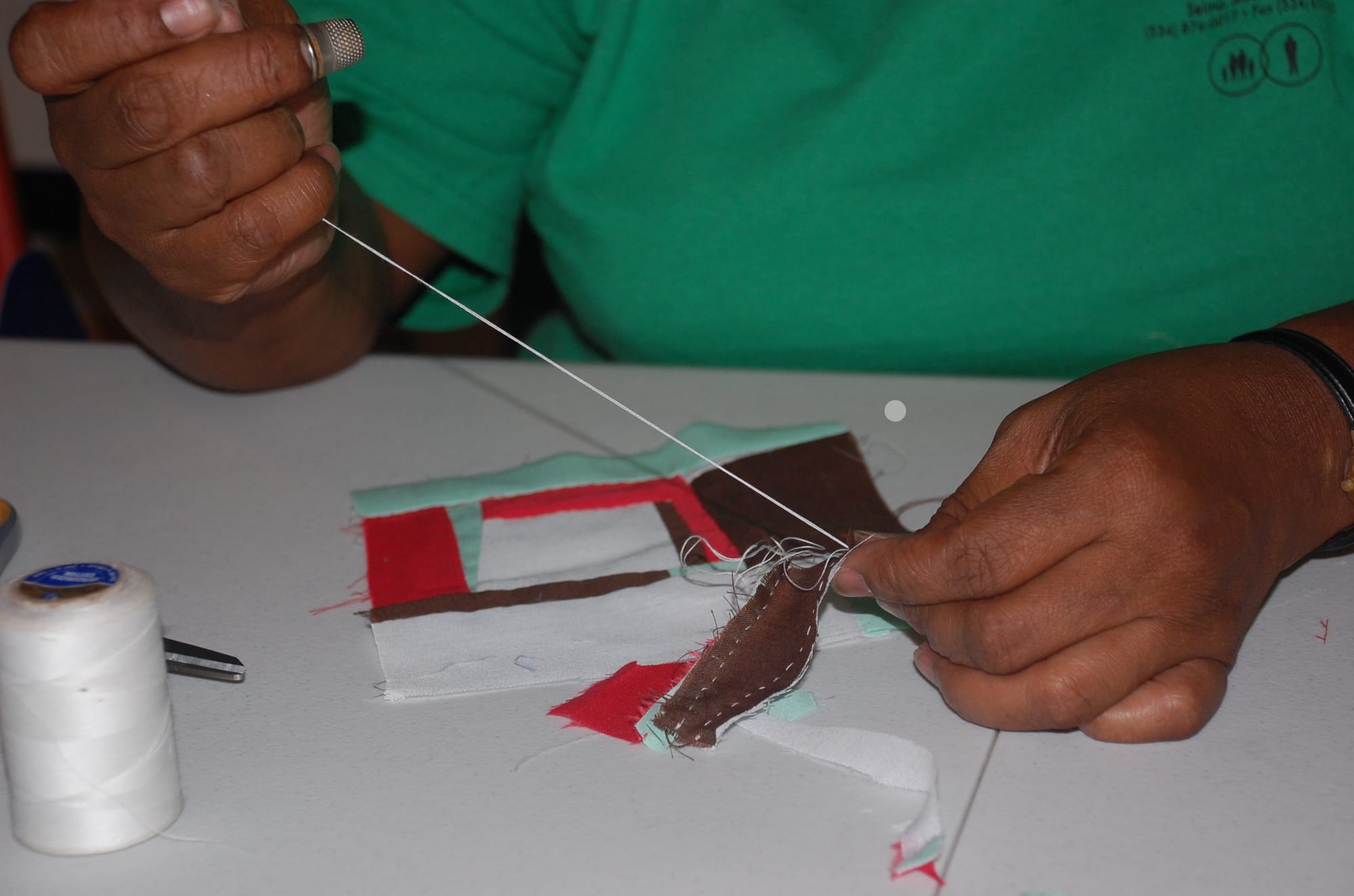

Birthed out of the need for warmth, the enslaved women of Gee’s Bend started piecing together scraps of fabric (think old curtains and corduroy pants) to make quilts in abstract patterns. Designs that had never been seen before on quilts. The patterns and piecing styles were passed down over generations, surviving slavery, reconstruction, and Jim Crow. During the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, the quilters organized themselves and began to sell their quilts throughout the U.S., gaining recognition and (eventually) economic independence. Today, authentic Gee’s Bend quilts are sold for $500 to $13,000. The quilts have been exhibited in museums across America. In 2006, the U.S. Postal Service even issued ten commemorative stamps featuring images of Gee’s Bend quilts. And the official portrait of former First Lady Michelle Obama was inspired in part by Gee’s Bend quilt designs.

Today, Gee’s Bend is an isolated, all-black community of about 550 people, and the quilts are still being made there. Many residents still carry the Pettway name, though due to illiteracy and inaccurate census records, the name has adopted many iterations. Pettaway, Petteway, Petway, etc.

I first heard the story of Gee’s Bend from my mom, who was born Barbara Pettaway in Fairhope, Alabama in the 1950s. In 2008, we travelled to Gee’s Bend together with a few other relatives. (Side note: The only reasonable way into Gee’s Bend is by ferry, a service that was discontinued by county officials in 1962 when Gee’s Bend residents started to take the ferry into town to attempt to register to vote. The ferry would remain closed for over 40 years.)

We explored all 2.6 square miles of the community. We visited the disused school building, drove past the shanty pool hall, saw the post office (which wasn’t there until 1949), and the tin-roofed fire department. We spoke with residents and spent time with the quilters. I walked through the Pettway Cemetery, cognizant that the names engraved on the stones mean more to me than I will likely ever know.

A few photos from my visit to Gee’s Bend in 2010.

That’s the excruciating thing about black history in America. It’s broken in two places—in its experience and in its memory—and neither are clean breaks. It’s a violent and incomplete history. An amputee. There are parts you can feel, but when you look, there’s nothing there. Just shadows of names, dates, places, a few photographs. But it goes dark before it should. And somehow the quilts of Gee’s Bend blanket that darkness with a kaleidoscope of patterns and colors, not unlike the Pettway family tree.

I am proud to be a leaf on a tree with such a strong root system. I may never dig down far enough to see those roots with my own eyes or hold them in my own hands, but I know that the eyes and hands that came before me saw them and held them with great determination and love. And I’m thankful.

When I was about 12 years old, my grandmother, Hattie Pettaway, gave me a patchwork quilt she had hand-sewn from scraps of old fabric. My friends laughed at the triangular sliver of skull and crossbones in one corner, but I cherished it. Fifteen years later, Grandma sewed another quilt for me out of a pile of old scarves I was throwing away. At the time, I thought she was just keeping herself busy. But now I know that there was more to it. Grandma was doing what the Pettway women have always done. Turning scraps into legacy and passing it on. It was instinctive. In her blood. My sewing skills are sub-novice, but I plan to keep the legacy alive by passing down the skull and scarf quilts to my boys.

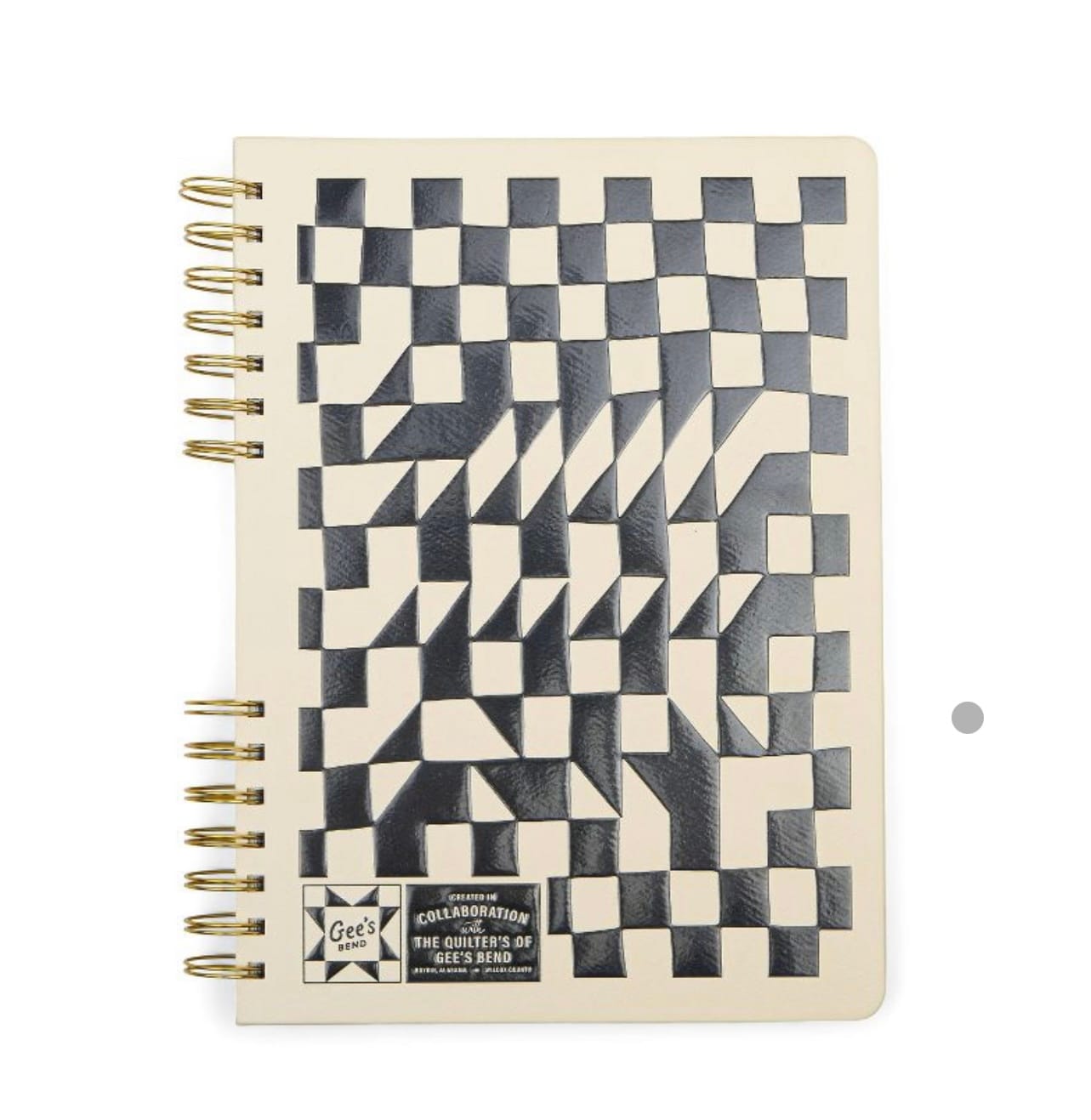

This year, Target partnered with Gee’s Bend quilters to produce an affordable line of clothing and accessories for Black History Month. Pillows, throws, tote bags, journals, hoodies, etc., all designed by Gee’s Bend quilters. I was shopping for groceries on the Target app when I saw these items and thought, “Wow! Mark Pettway could have never predicted this.” That the ancestors of his slaves whom he forced to work without pay would one day work for themselves. Put their fingers to fabric and find a way to transform scraps of oppression into beautiful tapestries. Into art. The quilts started as a means of keeping warm in Alabama’s low country, but today they hang high in museums and now in the aisles of a $66 billion retailer. Artifacts of cultural identity made by hand on an obscure patch of land with a painful history.

Gee’s Bend items available at Target.

It’s hard for me to ignore the profound metaphor of the Gee’s Bend quilts. They are not a part of black history, they are black history. A product of hard work and ingenuity created largely in isolation. Asymmetrical patchwork imbued with unexpected unity. Culturally rich and historically significant. That’s black history. From subjugated to celebrated. From the dark corners of the low country to the forefront for the whole country to see.

Fourth-generation Gee's Bend native Teresa Fuller put it this way: "Target has introduced our legacy to the world. We've gone from tradition to fashion, and that's a major thing."

My family history is now a brand at Target. If you’re shopping there this month, peruse the Black History Month section to see and hold and celebrate what we‘ve done with scraps.